Two surprising findings from new imagery of ancient human remains from Pompeii

It was with a force greater than an atom bomb that Mount Vesuvius erupted and blotted out Pompeii in 79 A.D.

Or, not blotted out, exactly.

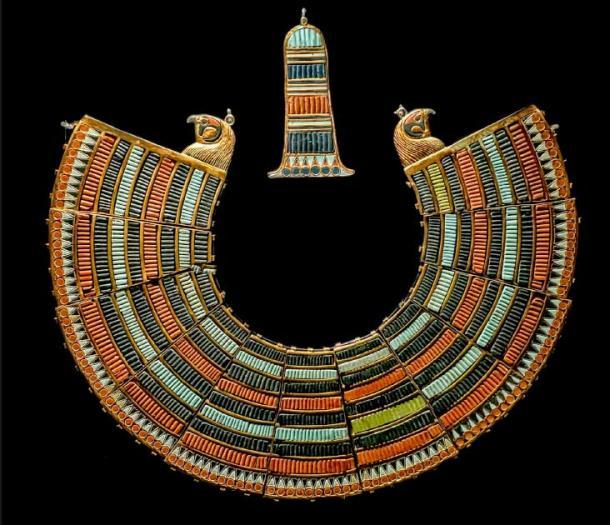

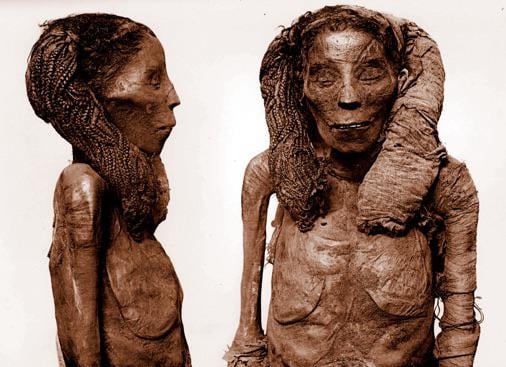

The city’s destruction, and the thing that has kept Pompeii so fascinating over the centuries, entails a paradox: The surge of ash and hot gas that blanketed thousands of victims also, simultaneously, preserved their bodies—along with their colorful art, sparkling jewelry, wine jugs, scrolls, and other cultural remnants.

Now, scientists are using new imaging technologies to examine in detail the bones and teeth of those killed in the blast.

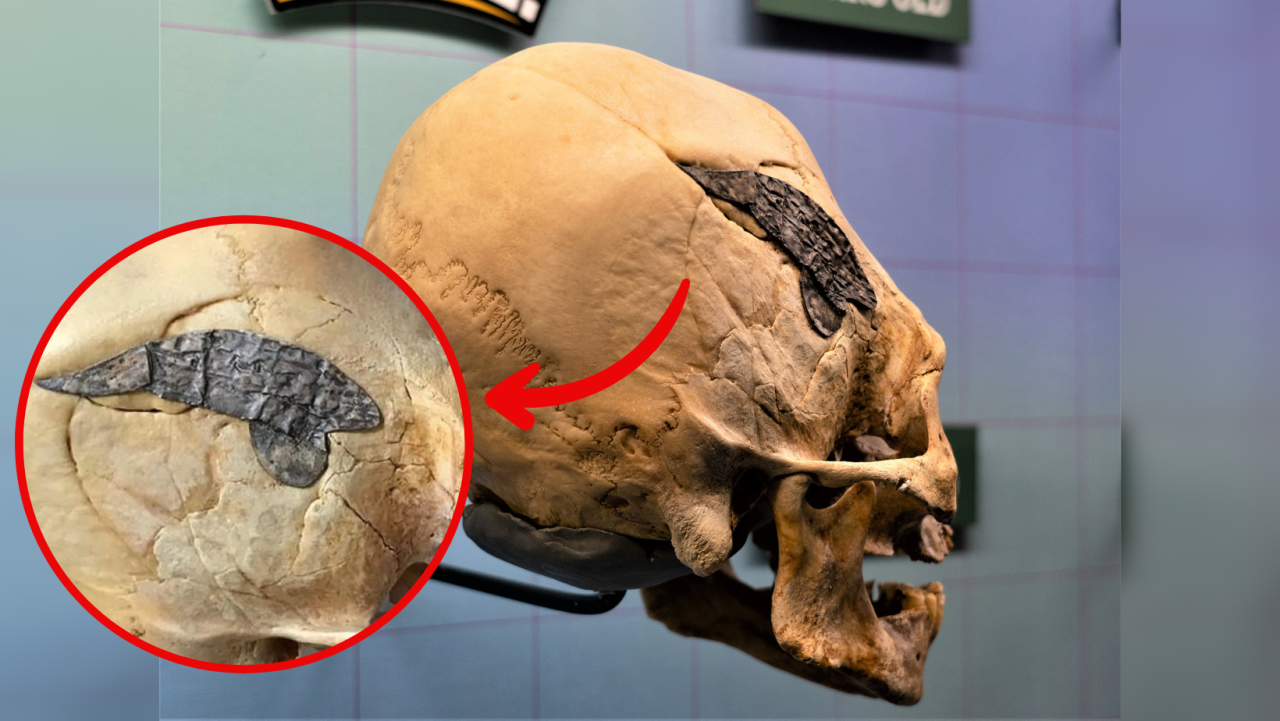

Detailed casts of Pompeii’s victims—made by pouring plaster into the small cavities in their ash-encapsulated remains—have long prevented sophisticated scanning of this nature. The 19th-century plaster is so dense that today’s standard imaging technology can’t distinguish between the thick outer cast and skeletal pieces inside. But researchers recently used a multi-layer CT scan to obtain imagery never before possible, then used software to make digital 3-D reconstructions of skeletons and dental arches.

The initial images reveal two major surprises.

For one thing, these ancient people had “perfect teeth,” according to Agenzia Giornalistica Italia, a discovery that scientists linked to a healthy diet and high levels of fluorine in the air and water near the volcano.

The scans also support a theory that many of those who were killed after the eruption died from head injuries—caused by falling rock or collapsing infrastructure—and not from suffocation.

This squares with the famous account by Pliny the Younger, who wrote of his uncle’s death after the eruption in an account that is treasured by historians. Here’s a portion of one of Pliny’s letters, translated from Latin by Betty Radice:

They debated whether to stay indoors or take their chance in the open, for the buildings were now shaking with violent shocks, and seemed to be swaying to and fro, as if they were torn from their foundations. Outside on the other hand, there was the danger of falling pumice-stones, even though these were light and porous; however, after comparing the risks they chose the latter. In my uncle’s case one reason outweighed the other, but for the others it was a choice of fears. As a protection against falling objects they put pillows on their heads tied down with cloths.

The smoke and ash that poured out of the volcano was likely still stifling to those who experienced it. In the early 1990s, when researchers uncovered the first remains found at Pompeii in many decades, archaeologists determined that some of the victims had tunics wrapped around their mouths as make-shift masks. Pliny the Younger described victims surrounded by broad sheets of flame, the air reeking of sulphur and the sky darker than night.

The latest findings build on an astounding body of knowledge about Pompeii. “Because of careful scholarship, we collectively have been able to get beyond the study of the victims’ death and have opened up exciting information about what the victims’ lives had been like,” said Roger Macfarlane, a professor of classical studies at Brigham Young University. “And, so, any technological development, such as CT scanning of the skeletal remains of those who perished in 79 A.D., promises to introduce potentially interesting new evidence about how those people existed before their death.”

Over the centuries, researchers have discovered unbelievable artifacts: erotic murals on walls, emeralds, coins, marble busts—and, in one case, an entire oven filled with dozens of loaves of bread still inside. Other food scraps found in Pompeii’s ancient drainage system have suggested the city’s wealthy residents dined on delicacies that included sea urchin, flamingos, and even giraffe.

The 79 A.D. eruption of Vesuvius was, as Pliny the Younger wrote, “a catastrophe which destroyed the loveliest regions of the earth.” But before that Pompeii was a vibrant city full of people who lived and, in one sense, continue to live, centuries after they died.